The Poor Law Records for Marden have been extracted by Eunice Doswell from a CD, transcribed and published by the Kent Family History Society, which contains records for Mid Kent. We greatly appreciate their help in making these records available.

To access our records click on Search the Archives in the menu above. To see the abbreviations used in these records please click on link.

The Poor Law Records contain details of the inmates of the Marden Workhouse or Poorhouse as it was often known. These records cover 1654 – 1843. In the latter year, the passing of the New Poor Law Act changed the organisation of workhouses.

1654 – 1700 shows 17 records

1700 – 1750 shows 96 records

1750 – 1800 shows 515 records

1800 – 1843 shows 625 records

Admittedly some of these are double entries and are under both names, but these numbers make very obvious the marked increase of applications for relief.

The greatest number of these entries concern illegitimacy. Women were pressured into declaring the name of the father so that he could be made liable for the maintenance of the child, and you thought the Child Support Agency was something new!? Travelling long distances was not uncommon, with Ann Parker naming William Bactra, a pilot of Limehouse in 1840, as the father of her expected baby. To encourage marriage & also to avoid paying child maintenance, in 1801 the Parish paid the pregnant Sarah Mepham of Marden & Thomas Marten of Brenchley one guinea to get married. In another case they paid for a marriage licence for George Burn & Fanny Price in 1815. Emigration was also used as a solution with 52 people from Marden having their passages paid to America in 1832.

The next largest number of records involve settlement & removal. Again large distances could be involved with Elizabeth Jones (alias Ferry) & several others being sent back to Lincoln. Swansea & Hereford are also mentioned.

Reading these records may provoke many thoughts, especially how lucky we are today, yet in other ways how little has changed.

Abbreviations used for the types of documents are :-

B = Bastardy Records

BB = Bastardy Bond

BE = Bastardy Examination

BO = Bastardy Order

BW = Bastardy Warrant

E & R = Examination & Removal

R = Removal

S = Settlement

SE = Settlement Examination

English Poor Law

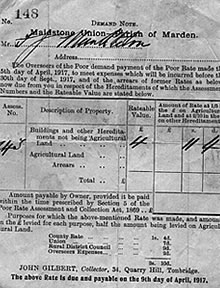

Monasteries were the first organisations to provide care for the poor. The actual workhouse had its origins in the 1597 Poor Law Act, where parishes were responsible for their own poor. In small parishes the Vestry, consisted of 2 churchwardens, 2 overseers for the poor and a constable to carry out their orders. These posts were filled by local people, but as they were unpaid no one wanted to do this for very long. Towns had almshouses for those unable to work and a corrective establishment for those unwilling to work. Each parish levied a poor rate according to the value of your property, which was collected by the overseers. This was collected twice a year with the overseers trying to calculate how much money would be needed for the coming months. Our Rev. Andrews was very worried about the high poor law rate Marden needed in 1801, but on his death 10 years later, it was discovered that we were more generous than neighbouring parishes, and so reduced the amount of relief given. To be a pauper you had to be poorer than the poorest in the land. Rogues & vagabonds could be put in the lock-up or legally have stones thrown at them to send them on their way.

Parish relief was dependent on settlement, to which everyone had a right, either by birth, apprenticeship, work or marriage. Therefore parishes were very keen to shift the responsibility for their poor elsewhere. They might try to apprentice young people in another parish. Two sorts of relief were available, indoor & outdoor relief. Both were there for those without work, those who refused to work & those unable to work. Indoor relief meant going to the workhouse and outdoor relief supported families in their own homes, this being the larger percentage of support.

Charities frequently existed to help the poor, often where richer members of the community provided for the poor after their death. The Maplesdens left land which earned an income for their charity. Alms might also have been collected at Holy Communion.

From the time of the Napoleonic Wars onwards life became much harder for the poor. Few new workhouses were built to meet growing demand, the cost of food rose enormously and an economic depression followed. There were the Captain Swing riots in Kent in 1830/1 protesting against mechanisation in agriculture. The Poor Law was flexible but open to abuse, so the New Poor Law Act of 1834 gave more central organisation. To try and curb misuse of relief, the outdoor poor were offered the Poor Law Test, which meant they were offered the workhouse or nothing at all. Locally the workhouses then came under the Union of Maidstone. The overseers were replaced by Guardians of the Poor Law Board. The 1881 census shows a number of people born in Marden residing in the Coxheath Workhouse.

| Attwood William | U | 74 | M | Pauper | Agricultural lab. | |

| Baker William | U | 33 | M | Pauper | Agricultural lab. | Lunatic |

| Chittenden Chambers | W | 78 | M | Pauper | Agricultural lab. | |

| Highsted Ann | U | 56 | M | Pauper | ||

| Hissman Frederic | 1 | M | Pauper | |||

| Hope Edward | U | 29 | M | Pauper | Agricultural lab. | Lunatic |

| Laddains James | W | 75 | M | Pauper | Agricultural lab. | |

| Richards William | M | 73 | M | Pauper | Agricultural lab. | |

| Russell Charles | U | 51 | M | Pauper | Agricultural lab. | |

| Sharpe Thomas | W | 75 | M | Pauper | Agricultural lab. | |

| Smith Caroline | U | 30 | F | Pauper | Imbecile | |

| Taylor James | W | 71 | M | Pauper | Agricultural lab. | |

| Usborne Samuel | U | 64 | M | Pauper | Agricultural lab. | |

| Verrall John | W | 85 | M | Pauper | Agricultural lab. | |

| Walter Jacob | U | 17 | M | Pauper | Imbecile | |

| Webb George | W | 80 | M | Pauper | Agricultural lab. |

In the early 1840s there were particularly bad harvests and there wasn’t room in the workhouses for all the able-bodied needing a bed. Victorian records show the lowest wages were paid to agricultural labourers and combined with large families this caused severe hardship for rural communities. Some kind of nursing & medical care could be provided in the workhouse. One of our doctors caused a rumpus when he was accused of sexually assaulting a female inmate. In such a small workhouse as Marden’s the sexes would not have been segregated. Official diets were introduced in 1836, perhaps Oliver asking for more was not generally true. Outdoor relief might have included a small allowance, payment of rent and some food & clothing. School fees might also be paid. A room in Marden’s workhouse was used to teach the ‘3 Rs’ with a schoolmaster being employed for this. Widows were encouraged to work, maybe parish nursing, washing or spinning with the provision of wool. They were furthermore encouraged to marry again. Men might also be sent out to find work or given a pile of stones for road mending. Bridge repairing & clearing ditches were jobs often given to the unemployed. The elderly would have their funeral expenses paid.

By the end of Victoria’s reign the solution of workhouses for the poor had become a very expensive business. So evolved the state funded system of benefits which we have today and the demise of the workhouse.

3 DVDs of documents from the Parish chest are viewable on the computer in the Heritage Centre, and are presently having their information put onto a database so they can be added to the searchable Archives.