Graham Tippen recalls the layout and activities of Marden station and goods that passed through it:

Graham Tippen recalls the layout and activities of Marden station and goods that passed through it:

The coming of the Railway, as I mention in my opening page, was one of the most significant events in the history of Marden and opened up the village and local farms and businesses to far greater opportunities for employment and trade than they had ever known before.

In terms of trade – the sending and receiving of goods and supplies – the South Eastern Railway and its successors provided Marden station with a good range of sidings and facilities right through from the opening of the station in 1842 to their closure and removal over 120 years later in 1963. Even after then, express parcels and priority goods could be sent from the station itself until the early 1980s.

Layout and Facilities

There were 4 sidings in what is now the upper car park, plus a siding to a goods shed and two ‘refuge’ sidings. I will add a plan of these to make the following description easier to follow shortly.

The ‘long siding’ ran adjacent to the churchyard with, just below where the black metal footbridge now stands, cattle-pens used for loading and unloading livestock. You can still see the entrance to these pens across the Station Approach from the Station Master’s House (now Old Station House) with the notice ‘Penalty for not shutting gate – £2’ on the anodised metal gate.

In earlier days, through to the last World War, cattle would also have been driven down to the pens along the path that runs between Shepherd’s House and the Wesleyan Chapel (Vestry Hall). Earlier still, before Linton View was built in the early years of the 20th Century, a third route to the pens existed directly from Marden market (subsequently Tippen’s and later Tomkinson’s yard between the Unicorn and White Lyon House).

The other two longer sidings here ran parallel and were just slightly shorter. These were mainly used for coal and bulkier traffic, where horse and carts and, in later years, lorries could draw alongside for loading and unloading. Botten & Luck, R Miskin & Sons, and Finch & Preston were 3 coal merchants all based in Marden who received coal this way and even in the early 1960s most days would find local men like Ken Hollamby, Howard Luck and his Dad, Charlie, or George Boorman shovelling, weighing and bagging up loose coal from 12 ton coal wagons into 1 cwt sacks and stacking the sacks into neat piles in the Station Yard. Rarely was anything stolen and each firm knew whose pile was whose.

What is now the lower car park was Miskin’s main coal yard, with large amounts of loose coal and coke stored here. This would have been shovelled, loose, into carts and carried down to the lower yard until needed. Other materials such as logs were also stored here.

There was also a short siding here ending in a loading ramp for the off-loading (or more accurately end-loading) of anything on wheels or legs. The remnants of the ramp are still noticeable, if you peer over from the ‘up’ platform where the metal railings meet the high wooden pallisade fence.

Perishable goods, or those of greater value were provided for by a goods shed, which was equipped with a small hand-operated crane. This was to the left of the main station building and the siding that served it ran in behind the up platform. The banking behind the lower car park formed its foundation.

Lastly, there were 2 ‘refuge’ sidings where slower trains could be shunted back to let an express pass. The one on the up line was also used for shunting the sidings and ran as far as Maidstone Road arch. The one off the down line ran back to Pattenden Lane arch.

The Pick-up Goods Train

The number of these varied over the years; mostly there were 2 a day; one in the early morning and the other early evening. Wagons for Marden will have been sorted at Ashford yards along with those for Pluckley, Headcorn and Staplehurst, having been brought to Ashford in larger trains.

The pick-up goods train was one of the most endearing features of the railways, and a particular feature of rural areas. Having assembled its train, an elderly locomotive would make slow but purposeful progress along the line, picking up and setting down trucks at each station along the route. There was a sort of timetable, but it depended very much on the number of wagons to be dropped off or collected and the number and frequency of other trains on the line. This was the case at Marden, as to assemble its train in the right order involved forays from the sidings on to the main line that could only be fitted in around passenger services including expresses and continental boat trains. It was particularly problematic when shunting involved crossing the up and down lines. Regulations regarding shunting movements were strict: there would have been hell to pay if the Golden Arrow was delayed because there was a truck-load of coke sitting on the main line! These movements would all have been controlled by the signalman who had a good view of all the sidings from his box at the London end of the down platform. So sometimes the whole operation took 10-15 minutes; another time over an hour.

I often used to watch the evening goods as a lad, as it arrived at Marden about 6.45 p.m. – after tea, just before bedtime. The period I am relating is around 1957- 62, my years of relative innocence in the days when you could walk the streets safely and before I discovered women, beer and cars.

It went something like this. The bells would ring in the signal box asking the signalman to accept the train from Staplehurst box. He would ‘pull-off’ the up distant signal and the train would appear from under Maidstone Road arch (for railway enthusiasts, usually, at this time, pulled by a Wainright ‘C’ or O1 class engine: you can see both types at the Bluebell Railway in Sussex) that would wheeze to a halt with much clanking and buffering up of trucks at the platform.

The whole train would then reverse into the ‘up refuge siding’ before uncoupling the train where the trucks to be left at Marden were located. These would be brought back out on the main line and left between the crossover. The engine would then run forward on its own, clear of the crossover before reversing across to the down line but facing in the wrong direction. Next it would run forward ‘wrong line’ to the top of the crossing before reversing again back across to the up line, but now behind the Marden trucks rather than in front of them. Re-coupling, it would draw them back into the siding. Here, temporarily, the signalman left the shunting in control of the shunter that accompanied the train en route, as all the points in the yard were operated by hand levers. Slowly pushing the Marden trucks forward, the shunter selected the correct siding by operating the point lever and uncoupled the wagon for that siding using his shunter’s pole; the engine gave a gentle shove, the truck trundled off and the shunter ran alongside it. Once clear of the points he grabbed the wagon brake lever and released it, the wagon eventually rolling to a halt, or under the laws of physics and forces, stopping when it hit the buffers at the end of the siding or another wagon.

This went on with much chuffing backwards and forwards, whistling, arm-waving, tripping over coal scales, swearing, and missing the wagon brake handle until everything was in its place and there was a place for everything.

The whole process in the last 2 paragraphs was then reversed to remove the trucks that Marden had finished with and fit them back into the train ready for departure. The crew probably had a brew up at this point before they and their train ambled off towards Paddock Wood and I ambled off home.

This was a scene repeated at countless locations across rural Britain for years, a vital part of trade and commerce and now gone forever.

What Came and Went

Two items formed the majority of goods to and from Marden station: coal and agricultural products. Coal was, of course, solely inward but traffic relating to agriculture went both ways. As already mentioned, Marden had 3 coal merchants for many years. R Miskin & Sons’ main coal and coke operation was situated within the station yard and they had their offices opposite the station (now the Dental surgery) as well as a large corn and animal feed warehouse (the black wooden sheds occupied by Autobase). Botten & Luck’s yard was in Pattenden Lane (now Luck’s Way and Sovereign’s Way) and Finch & Preston operated from a small yard in Howland Road also now houses.

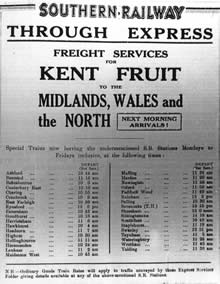

Outgoing agricultural traffic was mainly top fruit en route to wholesale markets in London and further north. At one point, it was reckoned that Marden shipped more fruit traffic by rail than any other individual station in the country and this in competition from road haulage firms like my father’s. A non-stop express goods, known as ‘The Bullet’ ran from Marden to London for several years.

Hops, dried and in pockets were also transported to hop factors in London prior to being sold to brewers in other parts of the country. Dozens of special passenger trains – hopper’s specials – would also have run every hop picking season to bring the workers down from London and return them afterwards. That is a story in itself to be told later.

Hops were a valuable crop, reflecting the huge demand for beer, the amount of effort and care needed in growing them and the labour intensity of their cultivation and harvest. Any damage (hops bruise easily) would have resulted in compensation claims on the Railway Company as would any loss of pockets in transit.

Hop pockets weigh around 1½ to 1¾ cwt each and stand around 6’ high so losing one is not that easy. However, in 1855 the station master was threatened with the sack if he did not make good the losses of hops.

In order to produce prime quality crops, of course, good husbandry of the land is needed. Manure, in various forms, became a major form of traffic for the railway. Marden was no exception, but not everyone was happy. Records show that in 1893 the good people of Marden, or at least those living close to the railway, complained to the Company of the nuisance caused by the smell.

Shoddy was a particular type of fertiliser for hops. Shoddy is wool waste and was obtained from the woollen mills, clothing and carpet factories of Yorkshire. As it was light and fibrous, it was loaded into box vans rather than open trucks, though the heat and dark of the van made for a perfect breeding ground for flies and other insects. It made life easy for those unloading it, though. You only had to open the wagon doors and the shoddy walked off on its own! Shoddy was still being used until a few years ago by Peter Hall on his organic hop garden. However, the use of non-organic dyes in carpet manufacture has ended its use.

Road Traffic Takes Over

Goods traffic by rail had declined after the war, though in overall terms millions and millions of tons were still carried nation-wide, especially in bulk. But as more motorways were built and lorries became larger and faster, the nation’s reliance on rail freight diminished, not helped by negative Government transport policies and British Railways’ constant ability to shoot themselves in the foot whenever possible. So it was that the majority of freight facilities at Marden ceased in 1963 with the closure of the sidings and subsequent lifting of the tracks. Some facilities continued to exist – express parcels, for instance, which had always been treated as a ‘passenger’ rather than ‘goods’ service and the Red Star service worked very well into the early 1980s. Wallace and Barr’s (later De Jaeger’s) nurseries used to send a special consignment of cut flowers from Marden station most evenings, an express parcels train stopping at Marden especially to collect these at around 8.00 p.m each evening (the nursery is now the new Highgrove Garden Centre). My own personal experience is of the current Mrs Tippen’s parents sending us a loft ladder by Red Star from near Stoke-on-Trent, where they live, shortly after we were married in 1981 (don’t ask why!). The Red Star lorry picked up the ladder from their house, took it to Stoke station from whence it made its way by express parcels service to Marden station from where Kate and I collected it and carried it home. All in less than 12 hours. I suppose some of the private dispatch companies will do the same nowadays, but at what cost!